(home)

The fallacy of "Separation"

By Eric SeymourIn the last issue, I examined the relationships and similarities between faith, religion, atheism, and agnosticism. I concluded that atheism is as much a religion as any other sect of faith, and that agnosticism is the only belief platform that is truly "humanist," if you will, in that it relies solely on the empirical evidence available to we humans through science. In fact, atheism admits the inability of the five human senses to reach beyond the natural world.

Now I consider the idea of "Separation of Church and State." This phrase is ubiquitous in public discussion, especially on secular college campuses. It is brought up every time someone wants to squelch public expression of religion. Dedicated atheists, more often than agnostics, cry "separation of church and state" whenever they don't want to be exposed to a religion other than their own.

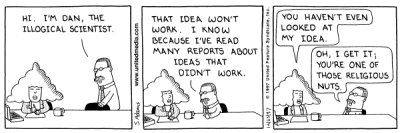

"Dilbert" Copyright 1997 United Feature Syndicate, Inc.

This odious phrase has been repeated so often that a majority of people, when polled, believe that it is found in the United States Constitution. In fact, it is most definitely not. What the Constitution does say about religion is contained in the First Amendment: "Congress shall make no law respecting an esablishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof."

The more I read that phrase, the more obvious the meaning seems. Simply put, the government (as embodied by federal and, by 14th Amendment extention, state laws) cannot restrict religious observance or favor one religious sect over another (such as by instituting a national church.) This interpretation is made even more clear when considering the background of the Framers of the Constitution, who came to the U.S. fleeing religious persectution, and the corrupt government-run Church of England.

For the most part, America's courts (and especially the Supreme Court) have decided cases properly in this light. While in 1962 they struck down mandatory prayer for grade-school children, they recently let stand the tradition of a prayer offered at I.U.'s graduation ceremony--a prayer which students are free to either join or ignore. The danger is when radical atheistic groups, such as the ACLU, can intimidate schools and communities into abandoning cherished traditions with the threat of expensive litigation.

There is nothing in the Constitution or in judicial precedent which requires public schools and other institutions to be "religion-free zones." An excellent example of this is the debate over the posting of the Ten Commandments in schools and courtrooms. Though the Supreme Court has ruled that requiring the Commandments to be posted is a violation of the First Amendment, their presence alone does not constitute endorsement of a religion. Were the Commandments authored by a great thinker such as Socrates, there would be no question about their presence. Simply because they appear in religious texts does not negate their place in legal history.

The idea of "religion-free zones" hits close to the center of the atheists' church and state separation campaign. It would be better termed "theism-free zones" that they want to establish, because (as explained in my previous article), the ideology they wish to promote is undoubtedly a religion. This can be seen from the promotion of evolution to the humanist philosophies being taught as early as elementary school.

Thus, "separation of church and state" as often expounded is highly suspect. As agnosticism is the one truly secular belief system, so the most proper position to be taken by the government, in light of the Constitution, is to acknowledge our history and traditions rooted in religion, and equally accomodate all faiths without favoring one over another. The atheists' goal to prohibit all religions where they touch public institutions is, in fact, an attempt to establish their own faith, whether they realize it as such or not.

Eric Seymour